The following is an excerpt from my book "Growing up with Spaceflight, Apollo Part Two" and is protected by Copyright 2015 Wes Oleszewski. No part of this may be republished in any form.

Taurus-Littrow

was the name of the landing site for Apollo 17. Located near the southeast rim

of the Moon’s Sea of Serenity, the site is a meandering valley between three

mountains called “massifs” (pronounced mass-eefs) in a range dubbed Taurus.

Littrow is the name attached to a nearby crater. Overall, the lunar EVAs would

be the longest ever and I could hardly wait for them to take place.

In order

to tape record the mission, as I had recorded Apollos 14, 15 and 16, I had been

saving up what money I could in order to buy what I believed to be “the best”

quality cassettes. In my arsenal I had two Memorex 120-minute cassettes and two

off-brand 60-minute cassettes. The Memorex tapes were for the actual mission

audio and the off-brands were to capture the “extras” that the news media may

just toss out here and there. Yep- I had it all covered from flight

broadcasting to contingency broadcasting. This time I would be using the best

of everything… right? Well, 30, years later in 2002, when I went to take my

carefully stored “Apollo Tapes” and transfer them to digital CD, the only ones

that gave me trouble were those expensive Memorex cassettes! They were so bad

that I had to take apart freshly bought modern cassettes and physically cut the

Memorex 120-minute tapes in half and then place the historic tapes into the

modern, off-brand, cases in order to get them to play. Meanwhile, my off-brand

cassettes from the Apollo and Skylab era still play just fine. Yet, in December

of 1972, I thought that I had it all covered.

It was

clear from the beginning that the TV coverage of the Apollo 17 mission would be

at a bare minimum. NBC, for example, came on the air at 9:45 pm, just 13

minutes before the scheduled launch time. For Apollo 16, NBC’s launch coverage

had started nearly a full hour before launch time. But Apollo 16 had launched

on a Sunday at mid-day when most network affiliates were showing old movies on

some sort of “Award Theater.” Apollo 17,

however, was supposed to launch in “prime-time” and most network executives

would have blood shooting out of their eyes at the thought of losing even a

minute of prime-time to cover a spaceflight. Thus, their Wednesday evening

viewers were now scheduled to missed only the end of "Hec Ramsey.” ABC and CBS were both on at 9:30 with launch

coverage; meaning that their viewers would miss the last half hour of "The

Movie of the Week" and "Medical Center" respectively. Either

that or the executives at those two networks had a greater sense of history and

the news coverage thereof, yet perhaps their eyes did not bleed as easily as

those of the suits at NBC.

It was

the plan of all of the networks, however, was to catch Apollo 17 getting off

the ground and into orbit, which was scheduled to take a total of 11 minutes

and 46 seconds, and then switching at the top of the hour to, “…our regularly

scheduled program, already in progress.,” Thus, the executives at the networks

would be keeping those prime-time advertising dollars and ratings points firmly

in their pockets as well as keeping the shooting of blood from their eyes to a

minimum. They would also rob us space-buffs of scads of spaceflight TV watchin’

in the process. After all, they figured, no moon flight had ever suffered any

sort of a technical delay, so their bet on the timing of this coverage seemed

to be a sure thing. The network suits would win, and the space-buffs would get

skunked once again. It was well planned by the three big networks- who were all

we had to watch in this era before wide-spread cable TV. Of course, events of

that Wednesday evening would cast immense suffering upon those network suits- especially

at NBC.

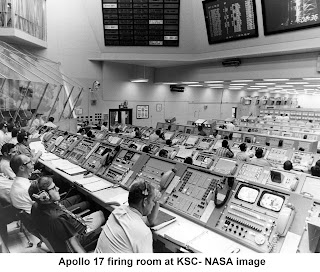

To those

of us not in the firing room at KSC, the final minutes of the countdown,

appeared to be moving along smoothly for Apollo 17. That included the crew

which consisted of Commander Gene Cernan, Command Module Pilot Ron Evans and

Lunar Module Pilot Jack Schmitt. What only a few people in the firing room knew

was that there had been a glitch at the 2 minute and 47 second mark in the count.

At that point the automatic sequencer failed to send the signal to pressurize

the S-IVB third stage’s liquid oxygen (LOX) tank. Controllers in the firing

room quickly moved to manually pressurize the tank and it did come up to

pressure, but their action was not swift enough to satisfy the sequencer and at

T-30 seconds the count was “cut-off” by the sequencer itself. There was a great

deal of confusion in the media as the NASA Public Affairs Officer, Chuck

Hollingshead, went into low-flow mode. The public was left guessing as to what

the problem was and whether or not there would be a launch tonight. It soon

became clear that that those “regularly scheduled programs” were not going to

be seen tonight and the well-planned broadcast schedule of those network executives

turned to toilet paper. Before the evening was over, they would lose their 10

o'clock hour and broadcasting "The Julie Andrews Hour,"

"Cannon" and "Search" all because of the Apollo 17 launch

sequencer. It was a rough night to be a TV broadcast executive, but an intense

night to be a space-buff.

AS-512,

the Saturn Booster that was supposed to send Apollo 17 to the moon just sat

there, venting LOX in that familiar white trail of vapor; commonly called

“goxing.” Of course, as the countdown clock stood frozen at the T-30 second

mark the controllers in the firing room were already working the problem and

actually had in place a “work around” solution. First, however, the countdown

and the sequencer needed to be recycled to the T-22-minute mark. This recycle

was a long involved, procedure-rich activity that would take nearly a full 40

minutes just to complete. Naturally, I was glued to our family TV as everyone

else in the family went to bed- with the exception of my dad who worked

midnights on the railroad. He just wished me luck by saying to me,

“I hope

you get that one off the pad tonight,” as he left for work.

Dad

always had a keen sense of how involved I was in spaceflight- even if it was

just through a TV set located 1,042.93 miles away from Launch Complex 39A.

Before

going to bed for the night, my mom left me alone in the living room with a

clear warning,

“No

matter how late you stay up for that tonight,” she half snarled in a firm

parental tone, “yer’ still gettin’ up and goin’ to school tomorrow.”

Indeed,

our deal had been that I could only stay home from school to watch the critical

parts of the mission that took place during school hours. Now she had me on a

technicality.

THE K577

RELAY

I kept CBS

tuned in during this phase of the mission. The other networks had good people

working the flight, but a good space-buff always kept Cronkite and Schirra

tuned in during an anomaly; provided, of course, that they could actually get a

CBS station. Meanwhile, the broadcasters did their best to make something out

of the nothing that PAO was spooning out. Unknown to us all was the fact that

the engineers in the firing room were all set to implement their work-around

and by-pass the sequencer. This was not a work-around in the sense that we

would see in the Space Shuttle era. This was a “bread-board” work-around. A

bread-board is a term for a type of tool used in electronics to study and test

circuits. Components are connected together with “jumpers” which consist of a

single wire with either clips or plugs on each end. Those jumpers can be used

to either connect or by-pass a given component or circuit. In the case of the

Saturn V sequencer, (and you electrical engineers reading this please forgive

me for over-simplifying here, but I’m writing for “normal” people), there was

no big master computer teaming with scads of hard drives. Much of what the

sequencer did came down to open relays and closed relays which executed each

action that needed to be done by triggering additional relays down the chain.

Each of these banks of circuits had a one-hole jack on one side and a similar

jack on the other. If the circuit, or its associated relay should fail to

trigger its task by closing, a technician could by-pass it with a switch or a

by-pass could be done by inserting a jumper with a banana plug on each end into

the two holes and thus “jump” across the circuit. The system hardware had actually been built

with this option in mind.

Basically what had happened was that when the

sequencer looked, at the speed of light, for the S-IVB pressurization trigger

it saw that K577, the “S-IVB LOX Tank Pressurized” interlock relay was open

rather than closed because it did not receive the signal to close. Although the

tank had been pressurized manually, the sequencer instantly, seeing the open

relay, cut-off the count. It never got as far as the switch that the technician

had closed. In the work-around, inserting the jumper would show the sequencer a

closed circuit at the open relay as well as the manual switch. The sequencer

would then be satisfied and simply move along and launch the Saturn V.

There

was, however, one last hang-up that delayed the launch even farther. The folks

at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama- who had

designed and constructed the Saturn V and the sequencer- needed to convince

themselves that the bread-board work-around would actually work safely. This was,

however, an expected delay by the ever cautious MSFC engineers and while the

team in the firing room at KSC waited, they successfully rolled the countdown

clock back to T-22 minutes and began counting down again. They could now go as

far down as T-8 minutes, where the chill-down of the J-2 engines in the second

and third stages had to be started. If they had no decision from Huntsville by

then, they would have to hold until the launch window was violated by through

what remained of the countdown. The count did indeed tick down to T-8 minutes

and then was held again awaiting word from MSFC.

Meanwhile excess hydrogen from the S-IVB and

S-II stages was being drained off and sent to a “burn pond” adjacent to the

launch pad where it was set aflame. Cronkite went to great lengths to assure

the viewing public that this was an intentional, necessary and totally harmless

fire. For more than an hour, everyone, from the news broadcasters, to the

firing room engineers, to a little kid in Saginaw, Michigan all waited tensely

for the count to resume.

Swing Arm

Number 9, which was the access arm to the command module, had been swung back

to the 12 degree “park position.” I wondered what it was like inside the Apollo

17 command module as the crew waited out the protracted delays. In his later

book, “The Last Man On The Moon,” Gene Cernan summed it up by reporting that

CMP Ron Evans, "… didn't think the delay was any big deal and he went to

sleep, his relaxed snore a deep undertone to the chatter on the radio net."

Somewhere

near 20 minutes after midnight Eastern time, MSFC finally transmitted their

blessing upon the KSC work-around that the folks at Huntsville who had

actually, themselves, designed into the system. The count began again at 25

minutes after midnight and progressed to the point where the S-IVB LOX tank was

to be pressurized. Again the console operator manually pressurized the tank.

Then when the sequencer looked toward the K577 relay it electronically saw the

jumper and thus concluded that the relay was closed. The count continued to

ignition and liftoff- which took place at 33 minutes past midnight.

It was

impossible to grasp the full glory of a Saturn V night launch through our

family television set, but the voice of Chuck Hollingshead as he called the

liftoff gave a good indication of what was taking place.

“It’s

just like daylight here at Kennedy Space Center…!” he shouted with the greatest

of excitement as the TV cameras that had focused on the vehicle were

video-smeared by the brightness.

NBC reporter/anchorman John Chancellor

afterward stated, “… …The whole sky became pinkish-green, like nothing I have

ever seen. It looked like a hazy day… it was as bright as the sun with a

flaming tail, maybe half a mile long… every car in the parking lot here, in the

middle of the night at the press site was clearly identifiable, the license

numbers could be read…”

Boost of

the S-IC first stage on Apollo 17 was completely nominal, yet Cernan sat in his

CDR’s position with the abort handle in his left hand almost daring the

guidance system to fail. That was because he knew that if he turned the “T”

handle counterclockwise he could activate the abort system and the escape tower

would fire, but if he turned it 45 degrees clockwise he could disconnect the IU

from its guidance duty and the Saturn V would be commanded by the CDR’s

joystick hand controller that was in his right hand. That would allow Cernan to

achieve every pilot’s dream and hand-fly the most powerful flying machine ever

to successfully take to the sky.

At staging the firing of the eight

retro-rockets shot out a brilliant halo of yellow flame that seemed to be a few

thousand feet across as it expanded in the near-vacuum of the upper atmosphere.

From that point on, Apollo 17 was little more than a white dot on our TV set.

For the last time an Apollo crew was thrown against their straps by the Saturn V.

It was also the only time that Cernan took his hand off of that abort handle,

he knew the jolt was coming and did not want to accidentally trigger an abort.

I

listened intently to all of the onboard reports and calls. “Mark, 1 Bravo,” an

abort mode, “Skirt Sep.” the point where the interstage skirt that had held the

first stage to the second stage separates. If it had not dropped away the crew

would have to abort using their escape tower. “Tower Jet,” since the skirt

departed cleanly, the launch escape tower was no longer needed, and was

jettisoned to save weight. Now all three astronauts could look outside. Prior

to this the Command Module had a Boost Protective Cover (BPC) over it. But,

when the tower jettisoned it took the BPC with it. Later in the second stage

burn as its fuel and oxidizer drained away, the stage’s level sensor was armed

and prior to that the crew was given an expected time for “Level Sense Arm.”

Level sense referred to a set of five probes in the S-II LOX tank’s bottom that

while whetted remained neutral, but when any two of these were uncovered they

signaled the Saturn V’s Instrument Unit (IU) to begin the sequence of engine

shutdown and staging. The system was not armed until late in the stage’s burn

to prevent a false shutdown. Level Sense, shutdown and staging for Apollo 17

took place as planned.

As

separation of the second and third stage took place a series of four retrorockets

buried in the S-II to S-IVB’s adapter ignited while at the same time two

posi-grade ullage motors on the stage S-IVB fired. These were all solid

propellant rocket motors that burned briefly; the retros to separate the two

stages and the ullages to seat the S-IVB’s propellant fuel and oxidizer. Once

expended the ullage motors were jettisoned to scrub weight. In the end the

S-IVB’s lone J-2 engine shut down some three seconds early, but Apollo 17’s

parking orbit was fine. Unlike previous lunar missions, Apollo 17 would alter

the timing of its Trans-Lunar Injection in order to help make up for the

delayed launch at the beginning of its third orbit some three hours after

launch.

One loss

caused by the delayed launch was that there would be no TV coverage of the

Transposition and Docking event- where the CSM separates, moves out, turns and

then goes back to dock with and remove the Lunar Module from the S-IVB. The

tardy launch left the earth-bound antennas that would normally receive the onboard

TV, out of position- so there would be nothing to watch. I packed it up and

went to bed with two thoughts heavy on my mind; 1) this was the last time that

humans would launch aboard a Saturn V and fly to the moon, and 2) my mom was

going to wake me up in about five hours so that I could trudge off to waste yet

another day in the mayhem of Webber Jr. High School.

For the

record, five decades later, I remember every detail about the launch of Apollo

17 that night- but I don’t recall a damned thing that went on at that “school”

the following day.