Fantasy

vs reality, which was once a definite line, is today becoming blurred.

It was the summer of 1971 as all across America we watched the flawless launch of Apollo 15 on our TV sets. You couldn’t miss it, because the launch was getting saturation coverage on all of the three television networks of that time.

This was a summer time mission so kids like me were out of school and could devote every second of our time to following the mission. Dave Scott, Jim Irwin and Al Worden really put on a show as they executed the first “J” mission to the lunar surface.

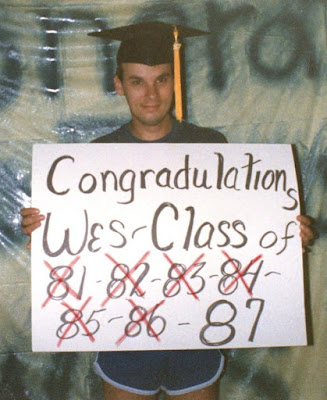

As a dazzled 14-year-old I watched and wanted to do that myself. Hey, if I could fly ants on my model rockets, why couldn’t I land ants on the Moon? I even built an odd little lunar lander and I called it, of course, “Falcon” in reverence to the Apollo 15 lunar module of the same name. It looked pretty cool landing on my living room carpet.

Of course, that was just kid’s fantasy. Today, however, the internet is blurring the line between fantasy and reality. One good example being that at this moment we have about the same chance of putting human back on the Moon that I had putting ants on the moon back in 1971.

Sure, we currently have one type of booster, the SLS, that is proven capable to fly people to the Moon. But we have no lander. And the proposals for a lunar landing vehicle are far closer to fantasy, then they are to operational hardware.

Sure, I can hear the voices of the fan-club right now chanting “Space X, Space X, Space X!” But it is part of that same crowd which gave us one of the dumbest ideas since lunar Gemini. It is called “Gray Dragon” and is supposed to be a Dragon spacecraft that can land on the Moon. Such may have more mythical qualities than my 1971 Falcon. Yet, the social media allows it to be defecated into the discussion as if it is a real possibility as opposed to Internet fantasy.

The other Space X lunar vehicle is their coveted Starship. You know, the same space vehicle that has blown up a half dozen times in the last year. It is the answer to all things when it comes to spaceflight… unless we’re talking about orbiting, or reentering, or landing. Their lunar design, however, is top heavy with a very narrow footpad span. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture it slowly toppling over and stranding the crew.

Of course, Space X has proven that they have mastered powered recovery and landing of huge boosters. Either on concrete landing pads at their launch site or on huge drone barges at sea. Yep… on nice hard surfaces that are really flat, and smooth... then they use that same method to land starship on the Moon.

It was during the early Apollo missions in which we learned that there is pretty much nowhere that the lunar surface is flat and smooth. That is especially so in the areas such as the lunar poles where we currently want to venture.

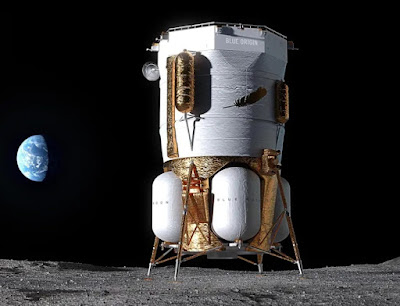

NASA, however, has one closer direction in which to go. Blue Origin has been developing its Blue Moon Mark I lunar lander. This un-manned device actually has hardware currently being constructed and is large enough to be modified and human-rated. It is slated to be ready to fly in late 2025 or sometime in 2026.The only snag is that the vehicle is designed to be boosted aboard their New Glenn rocket whose schedule is being protracted.

Yet, although not nearly as bad as the Starship lunar lander, the Blue Moon Mark1 has the same top-heavy design with narrow footpad span. Heck, my 1971 “Falcon” had a better foot pad span and it was designed by a 14-year-old.

Some speculate on the Internet that perhaps Space X and Blue Origin may “cooperate” to have the Starship, with its high Delta V, shuttling people and materials into and out of lunar orbit and Blue Moon going to and from the surface. However, we know that, A: these billionaire mega companies never “cooperate” with anyone- they just engulf and devour, B: Unless a fatter NASA contract is involved Elon doesn’t give a squat about the Moon- he is fixated on Mars. So, once again, the line from reality toward fantasy is blurred. SLS will send Americans to the moon in the near future, but they have no device to allow them to land and explore...and that is reality.

Thus, the

un-blurred bottom line is, again, we have the same chance in 2025 of again putting

astronauts on the lunar surface as I had for putting ants on the moon back in

1971.

L.jpg)