SCIENCE GARNISH

Apollo still had another three days on-orbit after the Soyuz had landed. There was actually no pressing reason for the remaining days on-orbit other than the fact that if the two spacecraft went up on the same day and then came back down on the same day it would make Apollo and NASA look as if they had been used for nothing more than a political tool; go up, do a political photo show and come down. That, however, is exactly what Nixon had in mind when he signed the ASTP agreement with the Soviets. In order to help avoid that flavor, NASA had garnished the mission with some post-handshake tasks. If looked at too closely all of it may easily be seen as make-work “science” to run for a few extra days on-orbit.

Of course with the DM still attached, the crew had something like a mini space station. Plus all of this gave Deke a few more precious days in space.

The laundry

list of "experiments" included some of the following:

"Extreme UV

Survey,"

“Helium Glow,”

"Helium

Absorption,"

"Soft

X-Ray,"

"Doppler Tracking,"

"Multipurpose

Furnace,"

"Electrophoresis

German,”

"Microbial

Exchange,"

"Geodynatics,”

“Biostack,”

"Crystal

Growth,"

"Stratospheric

Aerosol Measurement,"

“Electrophoresis

Technology,"

"Cellular

Immune Response,"

“Polymorphonuclear

Leukocyte Response,”

"Crystal

Activation,"

…and of course

who could forget, "Zone Forming Fungi."

If read too closely that listing may appear as text written for the purpose of prolonging content. Of course that is the mode that we are in at this point when talking about ASTP.

Additionally the crew had a list of 110 Earth observations to perform.

All of this added to the mission could make Skylab appear to be a cakewalk to the general public. Most of this, however, required very little crew interaction other than throwing a switch or opening a package. By reading the onboard voice transcription, however, it becomes clear that the crew spent a lot of the remaining flight just looking out the window. (Of course that could be translated in pilot terms to being a part of those Earth observations.) Had I known at the time that the crew was up there simply looking out the window, I would have been delighted. Deke Slayton had waited a long time for those few days and I hope he savored ever second of it. In his autobiography, “Deke!” he later said that he, “…wished there was a bubble turret on the spacecraft, so I could just sit up there and watch the world go by.” Years later the International Space Station would pretty much do just that.

APOLLO’S FINAL

SPLASHDOWN

My schedule for

splashdown day had me punching in at the Civic Center at 8:00 in the morning SWLC (Slob Working on the Labor Crew) time. I

was scheduled to knock-off at 4:00 p.m., which would have me home in time for

the splashdown. Our boss, however, had the day off and his assistant had to leave to go

to the dentist for an emergency procedure. It mattered little because there was

absolutely nothing to do in the building that day. Thus, we broke out the

Frisbees and spent the morning getting paid to zing them around the arena. One thing an arena that often hosted rock concerts has plenty of was discarded Frisbees. By

11:00 the building’s assistant manager came down and decided to just send us

part-timers home for the day. That put me home in time to catch the de-orbit

burn as well as the splashdown.

For the last time since 1971 and Apollo 14, I set up my recoding rig to capture the TV audio of an Apollo mission. My position in front of our basement TV set was a bit damp, but nice and cool, as I waited for any information on the ASTP’s return to Earth.

Oddly, considering the blanket of news coverage of ASTP, the de-orbit burn and CM/SM separation was not covered either on TV or radio. The SPS engine burned started at 3:28 and lasted for 7.8 seconds. Next, the separation of the CM took place at 4:44 p.m. basement time. For a moment I wondered if the network executives may skunk us space-buffs again in the same way that they did on Skylab 4 and not cover the splash-down.

At 5:00 sharp I was relieved to see Cronkite and Schirra on my TV set awaiting the splashdown. My problem was that for some reason UHF Channel 25, which was CBS, was not coming in well. I had to make the switch to VHF Channel 5 and NBC. There John Chancellor, and Roy Neal were doing the broadcast in the company of Alan Shepard.

As the CM came out of blackout and went into the nominal descent profile everything went exactly as planned. We actually had an image of the CM dropping toward the ocean just a moment before the drogue chutes deployed.

Then we got to watch the entire parachute sequence. Apollo was putting on a real show for us space-buffs. Splashdown took place at 5:18 basement time and everything looked great.

Inside the CM, however, as it bobbed Stable 2 on the blue Pacific, the three astronauts were nearly choking to death and no one knew it.

There are only three eyewitness versions of the story of what happened during the reentry in publication, namely statements by Stafford, Slayton and Brand. Studying these, the issue interpolates into the following chain of events.

After reentry the communications system in the CM suffered a short circuit that caused a shrill feed-back type of noise to blast into all three of the astronaut’s headsets. The only way for the crew to talk to one another was to shout. Distracted, in part, by that problem, Brand neglected to throw the switch that would activate the automatic chute deploy. Expecting to see the apex jettison and the drogues to deploy between 24,000 feet and 18,000 feet, the crew quickly realized that nothing was happening and Brand immediately hit the manual deploy and the sequence began. In Stafford’s version of the story either Brand or Slayton were too distracted or could not hear Stafford give the call to kill the RCS, or Stafford simply missed the call himself. No matter who did not do what, the RCS system was left on, and as the CM was swinging wildly under the drogues the RCS jets were firing to try and stabilize the capsule. At the same time, the vent to allow fresh outside air into the cabin opened as it should. That open vent and those firing jets were never meant to mix. As a result nitrogen tetroxide from the jets was sucked into the cabin by way of the vent.

Ingestion of just 400 parts per million of nitrogen tetroxide can be fatal to an adult human, and in short order the gas was hanging like a yellow-orange fog in the cabin of the CM. All three astronauts were strapped tightly into their couches and could do nothing other than sit there as their skin burned, their eyes watered and their lungs began to clog.

Splashing down the CM flipped over onto its nose in the Stable 2 position with the astronauts now suspended face-down. Stafford knew that they were in danger and unstrapped, dropping nearly 10 feet into the Lower Equipment Bay. Grabbing and clawing toward anything that would allow him to climb, he stepped on switches and handles to get up to the emergency oxygen masks located behind his seat. Ripping off the cover he placed a mask onto himself, gave one to Slayton and turned to Brand. He found that his CMP was unconscious having been overcome by the gas. He put a mask onto Brand’s face and then hit the “High Flow.” Brand began to come around, but began thrashing his arms, knocking his mask off and clobbering Stafford in the process, and then Brand again lost consciousness. Stafford repeated the process and this time held Brand in a “bear hug” until he fully regained consciousness. Shortly thereafter Stafford activated the inflatable up-righting bags. In a few minutes the CM rolled back over into a Stable 1 position.

Although the

crew needed desperately to open the hatch and air out the cabin before their

oxygen ran out, when the first rescue swimmer knocked on the hatch window,

Slayton instinctively gave him the “thumbs up” signal indicating by mistake that

all was well. Stafford moved to open the hatch and Slayton stopped him.

“Goddamn, don’t

open the hatch! We might sink like Gus!” Slayton urged through his mask.

Apparently, the

trauma of Grissom’s lost Liberty Bell 7 was so engrained in Slayton that he

feared another such embarrassment more than choking to death in a poison

atmosphere. Stafford just reminded him that unlike Liberty Bell 7, whose hatch

blew off, Apollo’s hatch was connected and could be easily closed again if

water began coming in over the sill. He opened the hatch and allowed the fresh

air to wash away the nitrogen tetroxide.

Following their

being landed on the carrier USS NEW ORLEANS, the crew were taken to the sick

bay and hospitalized aboard ship as it set sail for Hawaii. All three recovered

from their chemical phenomena and in a few weeks were back to normal. The

doctors estimated that of that fatal 400 parts per million of nitrogen

tetroxide, the crew had taken in about 300 parts per million.

A SYMBOL OF

GROWING UP WITH SPACEFLIGHT IN THE 1970s

As I put away

my tape recording rig and stowed the three cassettes in my S.R.E.C. box, it

struck me that this was the end. There were no more manned spaceflights, at

least not until that pie-in-the-sky Space Shuttle started flying. Yet, there were

plenty of Congressmen, news orators and even planetary scientists who were

loudly calling for the cancellation of that Shuttle thing before it even got

off of the drawing board.

The enemies of

manned spaceflight had already gotten their way with Apollo, which had

demonstrated solid results in a very successful way, and now they were setting

their sights on the future and the Shuttle. The Shuttle, it appeared, would be

an easy target by comparison to Apollo and the general public in America did

not care at all. On July 24, 1975, it

truly appeared as if there was no future for manned spaceflight in the United

States. The only hope was the fact Nixon the NASA hater was now out of office

and President Ford appeared to be indifferent toward the subject of human spaceflight.

Perhaps NASA could quietly develop the Shuttle outside of the media spotlight

and make it a reality. I had my doubts.

Repeatedly we

were told that the Space Shuttle would be making its first flights in 1979,

just four years after ASTP. But, I was 17 years old and the distance between ASTP and the Shuttle was just over a quarter of my lifespan so far. That

seemed to be a very long time away. If anyone had told me then that it would be

more like six years before the Shuttle was flying I would probably have slipped

into a state of clinical depression. In the summer of 1976, I tried to get into

the Shuttle groove by buying and building an Estes 1284 flying Space Shuttle

model rocket. When launched, it spread itself across the bean field behind our

house. The future was indeed dim.

Nixon’s era of

“détente” with the Soviets did not last. In August of 1975, the Ford

administration met with the Soviets to further the easing of tensions between

the two super powers. Agreements were made concerning the sharing of

technology, trade, peaceful settlement of conflicts and human rights. Shortly

thereafter it became clear that the Soviets considered their agreement on human

rights to only apply outside of their borders. As the U.S. pressed the issue

with the USSR, détente began to unravel. Finally, in 1979, the Soviets invaded

Afghanistan and any feelings of détente simply vanished as the Cold War began

to get much colder. It would not be until after the fall of the Soviet Union in

1989 that the United States would once again look toward flying in space with

the Russians.

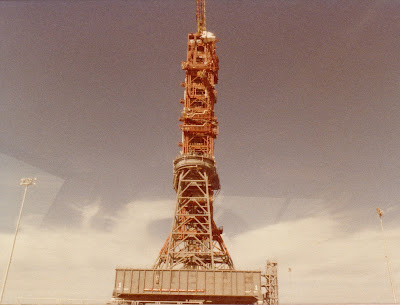

On January 28, 1978, I went on the bus tour at the Kennedy Space Center. Out on Pad B at launch Complex 39, the launch tower and milk stool upon which ASTP had launched back in 1975 still stood. Grass was sprouting through the cracked concrete and the tower itself was faded and weathered. Closer to the VAB the other two towers were being taken apart – the top two-thirds to be used for the Shuttle program and the bottom one-third scrapped. Yet, the ASTP Saturn IB launcher still stood at the pad. I asked the bus driver why it was still there and he said that ASTP had not budgeted to move it back to the VAB. They had the budget for the launch and that was all. He speculated that they would have to make room in the Shuttle budget to “clear” that pad. I was never sure if that story was factual, but at the time, it made sense.

When I stood on

the riverbank at Titusville in April of 1981 and watched STS-1, the first Space

Shuttle launch, in the foreground was that Apollo Saturn V launcher that had

been converted for the Saturn IB with the milk

stool. It had been used for Apollo, Skylab and ASTP. Now it was parked behind

the VAB, waiting to be scrapped – and years later it was. Somehow, its demise was symbolic

of growing up with spaceflight in the 1970s.

INSPIRATION

During that week and a half of the ASTP mission there was a news conference between the crew and President Ford. I missed it, but my brother captured it on my cassette tape. Later as I sat and listened to the tapes Deke Slayton was asked by the President what message he would pass along to America's school kids. His answer is 100% Deke...

"Decide what you wanna do, and never give up until you've done it."

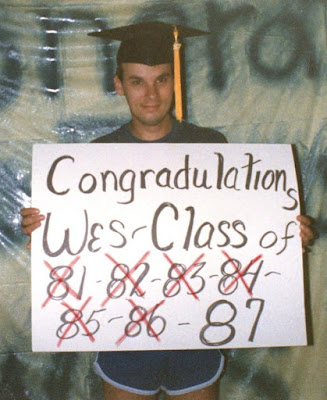

I would be a high school senior in just a few weeks and that simple message from a man who had gone along a hard and frustrating dozen years to finally do what he wanted to do, resonated for me. I had already decided that I was going to attend the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and become a professional pilot. I couldn't afford it, it was known as the toughest aviation school in the world, and no one thought I could do it. Even my high school guidance counselor said flat-out that I couldn't do it. It took me a decade to work my way through that university, but on August 15, 1987 I proved them all wrong. Along the way I always remembered Deke's words, and I never gave up.

This sign was prepared for me by my mom and my wife-to-be.

No comments:

Post a Comment