Tuesday, July 15, 2025

Apollo- Soyuz, as I lived it a half century ago Pt2

It was mid-July

1975 and gone were the days when I could set aside paying attention to school,

or anything else, and solely focus on a spaceflight. Now I had to “work.”

Somehow, work still never ranked up there as high as spaceflight with me. There

seemed to be this philosophical line between pushing a broom in an arena and

the peaceful advancement of human civilization.

Before leaving

for work on launch day of Apollo/Soyuz, I asked my mom to go down to the

basement TV, where I had the TV tuned to NBC, and simply push the “record”

button and then allow the tape to run out. I would handle the rest when I got

home. Of course, I went so far as to have her actually practice pushing the

button. Although she seemed a bit doubtful about the task, I assured her by

saying that with any luck she would not screw it up. Hey, you can have an ideal

kid, or you can have a space-buff, but you cannot have both.

I had spent the day before launch day at the Civic Center putting 3,000

chairs down onto the floor of Wendler Arena for a country and western concert.

Getting up early the following morning I had just enough time to watch some of

the Soyuz pre-launch coverage and then had to go back to the Civic Center and

pick up 3,000 chairs.

The rest of

America’s space-buffs saw the difference between

a Soviet launch and a NASA launch. The space news commentators were picking out

odds and ends, and in many cases guessing at what would happen next. Yet I was left in the arena with 3,000 chairs to manage.

NBC’s John

Dancy was reporting live from Moscow that the Soviet public was “very excited”

about seeing live television of a space launch, as well as live TV of the

Soviet launch control center. It was estimated that some 100 million Soviet

citizens watched the launch live on TV. One feature that did not materialize

was live video from inside the Soyuz. The Soviets normally had a video downlink

from inside the spacecraft, but moments before launch the Soyuz camera failed.

Soyuz was

launched in a slightly smeared TV presentation as a translator gave the English

version of the Russian calls.

“Ignition!” the

translator stammered, “the engines are powered up. The launch! The booster is

off! The flight is proceeding normally. The program maneuver of the booster

rocket has been given… 20 minutes into flight.”

Apparently the

difference between minutes and seconds was lost in the translation.

“The flight is

normal,” the translator continued, “the engine is operating in a stable manner…

there’s a slight movement of the booster, oscillation.”

A part of the

awkwardness of the translation was the fact that the translator was projecting

the words of both launch control and Leonov at the same time. No doubt our

launch communications sounded just as awkward to the Soviets. Also, if the

Soviet translator said anything wrong while narrating the mission the next stop

could be the salt mines in Siberia. Soyuz 19 was inserted into orbit as planned

and the next move was up to the United States.

Of course, I

missed the entire Soyuz launch because the fate of the free world hung on those

3,000 chairs that now had to be picked up. I rarely complained about work because

the pay was fairly good and I always kept in mind what my Advanced Electronics

teacher used to tell us when we complained about an assignment: “There are guys

in the salt mines who have put in eight hours already.” We did have the local

FM Rock radio station, WHNN, on the arena speakers, but they did not break the

music for news very often. I skipped my lunch hour in order to leave work early

so I could get home and watch the Apollo launch.

Arriving home I

found that Mom had accomplished her task exactly as instructed. Just moments

before the launch broadcast began I dashed upstairs to the kitchen to make an

iced tea and on the way past I congratulated Mom on having done a good job.

“Well, I’m not

a complete idiot,” she sneered in reply.

Heading back

down to the basement I told her that such a conclusion was still in question.

CBS was my

choice for watching the final Apollo launch. The Space Shuttle that NASA was

talking about seemed to still be pie-in-the-sky even if they did tell us it was

only four years away. As far as I was concerned, considering the political

attitude toward spaceflight over the past few years, this ASTP launch might

just turn out to be the last American manned space launch, ever. Thus, I was

going to watch Cronkite and Schirra and I was going to enjoy every second of

the launch. Perhaps the only thing better would have been to be at the Cape

myself to see it go.

At KSC the

weather was simply outstanding for a Saturn launch. Coverage of the launch

picked up at 3:30 Michigan time that

afternoon, and compared to the coverage given to the previous Skylab launches,

ASTP’s coverage would look like a marathon. The networks had brought in almost

anyone that they could find who had flown an Apollo to either give comments or

simply sit and look interested. NBC brought in Alan Shepard to co-host their

coverage with Jim Hartz and John Chancellor. Frankly,

Shepard was never comfortable being around the news media and it showed. I

stuck with CBS.

CBS’s technical folks presented both views at the same time as a diagonal split-screen for the first few minutes of the boost. Once the launch vehicle was too high to see much detail, they switched to just the inside view of the crew. The view was simply amazing. Space-buffs could see Brand, nearest to the camera, and Stafford, in the background; Slayton was not in the view. We watched, for the first time, as our astronauts threw switches and ran checklists and headed into space. Cronkite commented that he sort of expected the crew to be pinned to their seats. But Schirra, who had commanded the first Apollo atop a Saturn IB, said that the acceleration was so gradual and the training was so good that the astronauts were actually quite comfortable. Additionally, once staging took place the ride on the S-IVB stage was little more than 1g. From my point of view, however, this live shot inside the Apollo CM was fascinating. The Soviets had often used a TV camera inside the Soyuz, although its images were never seen live by the public. In a strange twist of fate, we put a camera in our Apollo because they had a camera in their Soyuz, then their camera system failed.

Monday, July 14, 2025

Apollo- Soyuz, as I lived it a half century ago Pt1

ASTP

After

nearly a year and a half of not having any Americans in space we space buffs

were actually looking forward to this thing called the Apollo-Soyuz Test

Project (ASTP).

Launched

on July 15, 1975 ASTP did not have its roots in science, discovery or

exploration. ASTP was, in fact, little more than a political exhibition

conducted in space. Amid the atmosphere of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty

of 1972, better known as SALT-1, the Nixon administration cooked up the

prospect to have an American Apollo vehicle rendezvous and dock with a Soviet

Soyuz spacecraft in Earth orbit. It would use up one of the final remaining

Apollo spacecraft, one of the final flight-ready Saturn IB boosters, and all of

the remaining Apollo budget. For Nixon, ASTP also would satisfy his desire to

best his historical political rivals. Too bad for him that he was compelled to

resign from the presidency in disgrace before ASTP was stacked in the VAB.

From the

perspective of a space buff Nixon’s legacy in spaceflight was that AS-210, the

ASTP Saturn IB, was launched on a Tuesday and on the following Friday 1,200

contractor workers at KSC were issued their pink slips. Sadly, it was only the

beginning of an aerospace industry-wide recession.

To most

enthusiasts of NASA and the U.S. space program, ASTP meant little more than

being able to witness an Apollo spacecraft fly again for the first time in more

than a year.

Without question the most exciting aspect of ASTP was the fact that the crew would contain one of the original seven astronauts, none other than Deke Slayton. Anyone who knew anything about NASA knew Deke’s story. He originally had been selected as the fourth of the seven original astronauts to fly, with his mission being one that would mirror John Glenn’s three orbits. He had named his capsule “Delta 7,” but as launch day drew near a single doctor looked at a minor heart fibrillation and decided to make it into a major issue. Slayton was grounded and ended up being the guy who selected new-hire astronauts and formed crews for missions. Then, some nine years after he had been grounded, Slayton began taking a regiment of vitamins to combat a cold and soon it dawned on him that his heart had not fluttered in months. After being examined extensively at the Mayo Clinic he was cleared for flight, and shortly thereafter he was cleared for spaceflight. The only problem was that all the remaining space missions were already assigned crews. Fortunately, along came one additional mission, which was ASTP. Slayton recommended himself for that mission. There was no one in NASA or in the spaceflight community who could have argued with that selection. Slayton’s only remaining problem was that he would have to learn to speak basic Russian.

Although there was very little technical advancement involved in ASTP, the political fluff was enough to draw the continued attention of the news networks. These same networks, who collectively ignored the splashdown of the Skylab 4 crew after their world record stay in space, now went all out to cover ASTP.

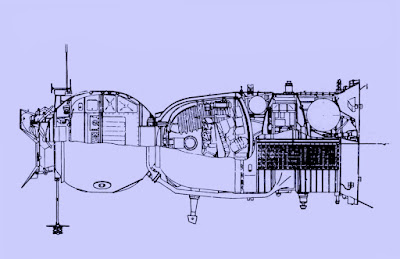

Now, in order for ASTP to actually happen, the ever-paranoid Soviets had to lift the covers. Additionally, the US demanded that our crews and NASA officials must be allowed to tour the top-secret Baikonur Cosmodrome launch site in Kazakhstan. Also, NASA insisted that US astronauts be allowed to examine the operational hardware such as the Soyuz spacecraft that would fly on the mission and the booster that would place it into orbit.

Although there was very little of ASTP for someone like me to get excited about, it did inspire Ravell to produce a 1:96 scale model kit for the event. The kit was based on their Apollo lunar landing kit of the same scale and it used the same CSM. New was the “International Docking Module” and a detailed 1:96 version of their long shrouded in secrecy Soyuz. I bought one of the kits in hope that it would annoy the Soviets.

WATCH FOR

PART 2

Monday, December 30, 2024

RETURN TO THE MOON

Thursday, February 8, 2024

SKYLAB 4 RETURN TO EARTH

THE FIRST SPLASHDOWN NOT COVERED ON TELEVISION SINCE IT HAD THE CAPABILITY TO DO SO

The following is an excerpt from my book "Growing up with Spaceflight- Skylab/ASTP" the text is protected by Copyright 2015 Wes Oleszewski and no portion of this may be republished in any manner.

Early on

mission day 85, the crew of Skylab 4 closed the hatch on the Multiple Docking

Adaptor for the final time and took their seats in the Apollo Command Module. It was February 8, 1974. Other

than a capture latch snagging, the undocking went off without a hitch. The only

real glitch was that the CM Reaction Control System’s (RCS) number two ring was

showing a helium leak when it was pressurized. Mission Control, suspecting an

impending fuel leak in the ring, decided not to use ring two and to simply

reenter on ring number one. If the crew were to have a problem with ring one,

Mission Control directed them to set the CM into a rolling reentry and proceed.

CBS radio’s spaceflight announcer Reid Collins, while describing the pending

reentry, stated that the crew of Skylab 4 would be coming in “on one ring and a

prayer.”

Since I had

taken the day off from school to watch this historic event on TV I had a whole

60 minute cassette tape ready to fill. I knew full well that it would be a year

and a half before the next manned American spaceflight, and so I was going to

catch every word of the TV coverage. It struck me that when the subject came up

on the morning news shows, there was no mention of when the networks would start

their coverage. At the expected time I was set up

and ready to go, but there was no coverage.

Those of us on

the outside who were growing up with spaceflight were not the only ones who

were screwed by the TV networks; the Skylab 4 astronaut’s families got the

shaft as well. Since there was no prior notice that the three TV networks were not going to cover the splashdown, the

families of the crew had invited guests into their homes to watch the event on

TV and celebrate. Instead of a joyful family moment that would be long remembered,

they were treated to a great disappointment far beyond what those of us in the space-buff ranks had experienced. Later that evening Walter Cronkite, while

talking about the Skylab 4 crew’s return, made it a point to highlight this

historic slight on his CBS evening news broadcast.

“Their landing

today,” Cronkite announced, “the first not covered live on television since it

had the capability to do so.”

In the book,

“Around the World in 84 Days,” Jerry Carr recalls that his son, Jeff, was so

upset by the fact that all of the TV networks had elected to ignore the

splashdown that he wrote letters to the presidents of NBC, CBS and ABC asking

why they had done so. Surprisingly, he received replies from all three, and essentially

they all said the same thing. The splashdown, although a historic event, was, in

their opinion, not newsworthy.

Thursday, November 16, 2023

SKYLAB 4: CONTEMPLATING A SHORT FALL DOWN THE BASEMENT STAIRS

The following is an excerpt from my book "Growing up with Spaceflight- Skylab/ASTP" the text is protected by Copyright 2015 Wes Oleszewski and no portion of this may be republished in any manner.

Considering that my family had now moved to the country and I was now in a good school, it was pretty hard for me to come up with a reason for staying home from school to watch and record the Skylab 4 launch. Previously my Junior High school had been such den of chaos that my parents were certain that I was learning more sitting home watching spaceflight on TV than I would “…in that damned school…” as my mom often stated. Now, however, being in a good school, I was sure that such was no longer the attitude of my folks. Of course, I considered playing sick, but being a lifelong asthmatic and generally sickly kid, my folks would easily see the difference. And an asthma attack that just happened to coincide with a Skylab 4 launch would be just too obvious for my parents to buy. I could plead and make big eyes, but at age 16 that would just look pathetic. Then, just as I was watching the evening news and contemplating a short fall down the basement stairs as a reason to stay home from school tomorrow, my Mom heard Cronkite talking about the next day’s launch.

“Is that goin’

up tomorrow morning?” she casually said.

“Yep,” I half

sighed in reply.

“I suppose,”

she asked rhetorically, “yer’ gonna stay home and record it.”

“Yep,” I

answered feigning confidence.

“Okay,” she

softly sighed.

Dang! That was

easy.

November

16th, 1973 Skylab 4 was set to launch at 09:01 and coverage of the Skylab 4 launch

began with assorted spots on the TV network’s morning news shows. Continuous

coverage of the launch started on CBS at 8:45 that morning and NBC started five

minutes later. Living in a new location, I found that NBC’s WNEM Channel 5 had

the best sound so I decided to record from there, but

changed over to CBS later just before launch. Deploying my implements

for capturing history, I took my normal space-buff position to watch the

historic launch that most of America would ignore in spite of network attempts of the news media to trump up an air of impending

danger surrounding the replacement of the launch

vehicle’s fins due to the discovery of some minor cracks.

At the Kennedy

Space Center the weather was perfect for a change as

opposed to the string of previous Skylab launches. Skylab’s 1 and 2 had jumped

from the pad and into the clouds in a matter of seconds, and likewise Skylab 3

had done nearly the same sort of departure. Now, however, clear skies and

unlimited visibility were the backdrop for Skylab 4. For the first time since

Apollo 7 the cameras would be able to follow the Saturn IB all the way up.

Considering that I had been held hostage in my fifth grade classroom learning

about the state bird of Iowa, or some such pointless

thing, during the Apollo 7 launch, this would be my first chance to watch an entire Saturn IB boost live on TV.

I was as giddy by

the clear weather as I was that it was a launch day. Also giddy that morning

were the three rookies in the Command Module. Gerry Carr later said that once

they were “closed out” with the hatch sealed and everything was quiet, he sat

up a bit from his couch and looked across his two crewmates. They all looked

back and they all “giggled like a bunch of

schoolgirls,” because they had been waiting so long for that moment.

Much of the

media focus on launch day involved the fin replacement efforts and the

perception that they may fall off at Max-Q. The countdown was normal and I

started my trusty tape recorder. At launch it seemed as if the flame was nearly

as large as a Saturn V, but the Saturn IB was tiny in comparison. It is interesting to note that the thrust of all eight of the IB’s H-1

engines combined was roughly equal to just one of the Saturn V’s F-1 engines.

On prior Skylab

IB launches the launch vehicle was not discernible in the haze, so this time it

was fun to watch. Cronkite kept exclaiming that this was the best we had ever

seen one of these (meaning a Saturn IB), and since I had not seen Apollo 7, I had to agree.

Cronkite

alerted viewers prior to Max-Q, which came at 69.5 seconds after liftoff. The

drama of the fins falling off had to be hyped up I guess. Of course, nothing at

all happened, no fins were lost. Then staging took place at 141.29 seconds into

the flight and we got a good view of the retro and ullage motors firing. Then, 29

seconds later, we saw the escape tower and boost protective cover jettison and

tumble away. Thereafter, Skylab 4 simply became a dot on

my TV screen. The ride on the S-IVB was described later by Gibson as being

“like an elevator.”

“Smooth as glass,

Houston,” Carr reported.

The S-IVB boosted

the CSM to just over 86 miles in altitude, where it pitched slightly downward

and flattened its trajectory to gain velocity. At 577.18 seconds into the boost

the single J-2 engine of the S-IVB shutdown and Skylab 4’s rookie crewmembers

were no longer space rookies.

The

following Monday I showed up as usual for my first hour Earth Sciences class at Freeland High School.

My teacher, Mrs. Warner, asked where I had been on Friday. Expecting the normal rolled eyes and

shaking head from her as I had seen in my previous school, I simply said that I had stayed home to watch the Skylab 4

launch. Instead of disdain, she put down her role-book and her eyes got wide,

“Oh man,” she

sighed, “I wish I could’ve done that.”

What a

difference moving to the country makes.

Monday, September 25, 2023

SKYLAB 3: SCRIBING LITTLE WHIMSIES

Skylab 3:

SCRIBING LITTLE

WHIMSIES

For most of the month of

September 1973 Skylab 3 seemed to, again, nearly drop from the news completely. Personally for me, a huge

transition took place in that same period of time. I was headed for high school and the high school that I had been

headed for was one of the worst in mid-Michigan. Knowing that a smart ass like

their son would quite likely get knifed within a week at that school, my

parents did the only thing that they could; they sold our house in Sheridan Park and the entire family

moved. Of course that up-rooting did not happen immediately. Instead, they

bought a home that was under construction in the little farm town of Freeland,

Michigan. I had an aunt and uncle who resided there and it was arranged that I

could start high school in Freeland and live with my relatives until our new

house was finished. Thus, I took up residence in the bedroom left behind by one

of my grown cousins and started attending a school where actual learning took

place and you could walk the halls in safety. We were on a “half-day” schedule

and classes started at 6:50 in the morning, but got out at noon. That left

plenty of time in the afternoons for space stuff. The only problem was actually

finding the space stuff. Jack Lousma conducted a protracted TV tour of the

Skylab in the closing days of the mission, but only small bits of that were

broadcast by the national news media. It was almost as if Skylab was not aloft

at all.

On September

25, 1973, the reentry and splashdown of Skylab 3 was scheduled for 7:19 p.m.

Eastern Time. I had spent much of that Tuesday afternoon listening to the radio’s

news reports of the progress of the returning crew.

I also had

plenty of time to ponder the fact that my cousin had spent some effort scribing

with a ballpoint pen little late 1960s hippie whimsies about “love” on the mortar joints between the bricks of his

bedroom walls. “How little I know about love, but how much I wish

I knew,” and crap such as that. Since I was not really a part of

that stoned, flower child movement, I found the writing to be a bit odd. Of

course, I was about to do something odd myself as I grabbed my tape recorder

and set it up to catch the reentry and splashdown of Skylab 3 on TV.

As I was

setting up the recording equipment my aunt came into the room and asked me what

I was doing. I replied that I was getting ready to record the Skylab 3

splashdown.

“Well, what do

you wanna do that for?” she asked condescendingly.

I explained

that I recorded all of the splashdowns.

“I don’t see

why you wanna do that,” she quipped, as if trying to motivate me to do

something more “hip,” perhaps

with a ballpoint pen.

I asked if she

could please excuse me because the coverage was about to start. She left the

room shaking her head and mumbling something about “nonsense.” Apparently she

thought my time would be better spent down in that bedroom, stoned and scripting

whimsies about “love” on the mortar joints between the bricks.

Splashdown of

the Skylab 3 crew went as advertised. CBS News had the best coverage with

Morton Dean and Wally Schirra hosting the event. I managed to get nearly a

half-hour of the splashdown activity on tape in spite of my aunt’s disdain for

spaceflight.

A few weeks

later my folks moved into our new house in Freeland and I moved out of my older cousin’s old bedroom. Before leaving I could not

resist taking a ballpoint pen and scribing a whimsy of my own on the mortar

joints between the bricks on the wall; something that would really make my

relatives scratch their heads if and when they ever read it.

“Houston,” I

scrolled in tiny letters, “the Falcon is on

the Plain at Hadley.”

Growing up with spaceflight in the 1970s, it was important to get the

last laugh.

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

M2-FI First Flight Anniversary

It was 60 years ago today that test pilot Milt Thompson piloted the world's first lifting body aircraft, the M2-F1 on its first flight.

Since the M2-F1 had to be very light weight it was constructed of plywood by sailplane maker Gus Briegleb.

So, on August 16, 1963 the M2-F1 was flying on its own. Although the steep "dive bomber" approach caught the observers on the ground, including Dale Reed, by surprise, Milt Thompson was fully in control. He did a simulated landing flair at 9,000 feet and then went right back into the descent profile. Landing exactly on his planned touchdown point he let the bird roll to a near stop before turning to roll clear of the desert runway.

When I was in high school in 1976 I designed my own lifting body "shape." It was a part of my 11th grade drafting class final project. While I was working on it- along with a model rocket booster and launch service tower with a retracting service structure (that I'm sure NASA stole from me), my drafting teacher the late Dan Craig came up and looked at the project.

"What's that wedge thing?" he asked.

"It's a lifting body," I replied as if he should know what I meant, "it's a wingless aircraft."

He simply shook his head and walked away. I go a "C" on the project mostly due to assorted tiny drafting errors, and on the lifting body he scrolled a message,

"Aircraft can't fly without wings- you should know that!"

Mine flew. Many years later my college roommate saw one of my lifting body balsa wood models and was so fascinated I gave him one. He went on to work as a NASA contractor at then Dryden, and Dale Reed's deck was just a short distance from his. So, he showed Mr. Reed my lifting body. The father of lifting bodies was impressed and said, "That would also make a great hypersonic shape."

But not constructed of balsa wood... of course

L.jpg)

.jpg)